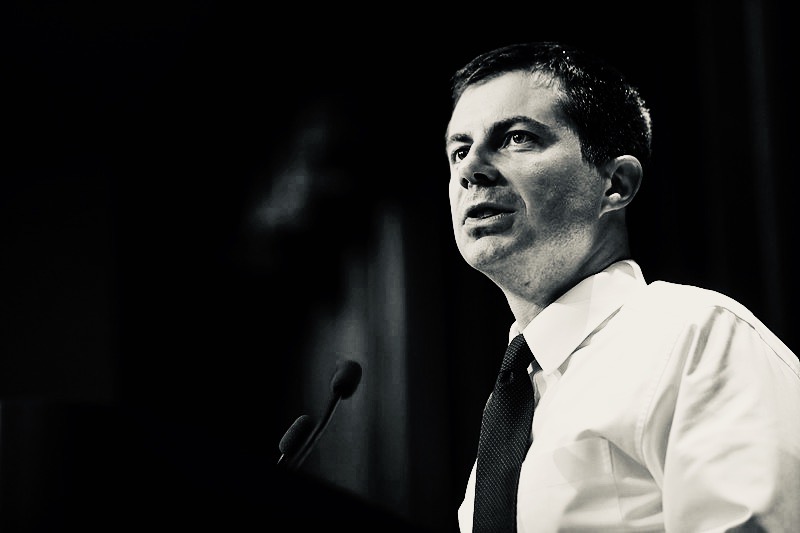

Generational change that isn’t: Pete Buttigieg embodies politics of the past

Pete Buttigieg is the youngest candidate in the race, and he won’t let you forget it. What is his message for the American people? His face. His candidacy is less about ideology and more about a nebulous idea of “generational change” — that he will usher in some grand new era of leadership in politics. Yet, Mr. Buttigieg’s track record as a politician is one of reticence and evasion. Despite his youthful posturing, Mr. Buttigieg partakes in the dishonest vacillation of old-fashioned politics.

A particularly egregious example of Mr. Buttigieg’s slipperiness is his equivocation on Supreme Court reform. Early in the race, the mayor turned heads when he signaled his openness to restructuring the high court. However, upon the release of his tentative plan to expand the court to fifteen justices, he received a whupping from the press. His political instincts kicked in, and he all-but-dropped the issue from his campaign platform.

Judicial reform, once a defining aspect of his candidacy, is now reduced to a one paragraph non-answer hidden away on his website. In that single paragraph, Mr. Buttigieg manages to weasel his way out of endorsing any specific plan at all — including the one he initially proposed! The only definite commitment he makes is to create a commission to study the issue once he’s elected. He’ll think about it.

But in terms of sheer ambiguity, his position on mandatory national service is his magnum opus. He first mentioned the idea in April as a way to unite American youth. In an extraordinary feat of triangulation, he said that he wanted “to make [national service], if not legally obligatory, but certainly a social norm, that anybody after they’re 18 spends a year in national service.”

The confusion is real, and consulting his website doesn’t help. While the plan’s name of “Service For All (who want it)” seems to point towards keeping service optional, he states that his overarching goal is to create a “universal, national expectation of service for all 4 million high school graduates every year.” Throughout the rest of the proposal, he never clarifies whether this “national expectation of service” will be enforced by law.

Of course, both of these issues got shunted away as Mr. Buttigieg transformed himself into a moderate. Mr. Buttigieg completed his pivot towards the center by releasing his own healthcare plan, “Medicare for all who want it,” which calls for creating a public option that would compete with the private sector. A ten page document was released in early September to fully explain the plan — but only a scrawny one-and-a-half pages were actually dedicated to explaining the public option itself (the rest discussed auxiliary reforms).

Even worse is that nowhere in the proposal does Mr. Buttigieg mention how much beneficiaries would pay out of pocket. That is one glaring omission, especially when, according to the Buttigieg campaign’s own statistics, 87 million Americans struggle with high out of pocket costs.

It also raises serious questions on how the Buttigieg campaign calculated the total cost of the plan, which it estimated to be about 1.5 trillion dollars over a decade. It makes no sense how the campaign could estimate the cost of the plan without knowing the plan’s out of pocket costs. There are two possibilities. One possibility is that the campaign has decided on the plan’s out of pocket costs, but does not want to reveal them to the public. The other is that the campaign has not decided how much patients will pay out of pocket, and simply conjured the total cost of the plan out of thin air. Either way, it is disingenuous for the campaign to come up with a price tag when they are not willing to be honest on how much the plan will cover for patient care.

This brand of vague politicking is nothing new; evasive political Houdinis have existed and prospered since the birth of the United States. Mr. Buttigieg isn’t bringing “generational change” to the old political playbook. All he did was put a young face on it.