Mastery of technical elements gives ‘Mank’ a polished, nostalgic feel

The latest film from director David Fincher, “Mank,” follows Herman J. Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman) as he struggles to finish the screenplay for “Citizen Kane” before his deadline. “Mank” also examines Hollywood culture during the Great Depression and the film industry’s role in the 1934 California gubernatorial election between Frank Merriam and Upton Sinclair.

“Mank” is about the making of Golden Age films — but to say only that would be an understatement. The movie is intended specifically for fans of those pictures. This is most clearly evident from its script, which is densely packed with references to movies of the era.

Most of the spoken references are quite subtle, framed as inside jokes between the characters. The implicit nature of these references makes sense; after all, most of the characters’ lives revolved around the film industry, so it would be strange if they did not casually bring up movies in their conversations. However, framing the references in this way made it difficult for me to pick up on many of them while watching. In fact, I had to watch the film again, paying very close attention — and even then, I’m sure several of them still went over my head. As this is a key component of the movie, this was certainly a drawback.

While “Mank” references many films of the era, the film draws its greatest inspiration from “Citizen Kane,” Mankiewicz’s most popular screenwriting success. “Mank” references “Citizen Kane” countless times, both visually and through dialogue, but even though its plot revolves largely around Mankiewicz’s race to finish writing “Citizen Kane,” the latter is never mentioned by name.

Still, it feels as if “Citizen Kane” is a cloud looming over the movie as a whole: its presence is always felt, but it is almost never at the forefront. This description is eerily similar to the way Orson Welles is portrayed in the movie. Welles has several scenes in “Mank,” but most of them are phone conversations checking in on Mankiewicz’s progress on the screenplay, during which his face is rarely shown on camera.

Interestingly, as Mankiewicz’s deadline draws closer, the visual references to “Citizen Kane” become more apparent, perhaps indicating how the screenplay is consuming more and more space in his mind.

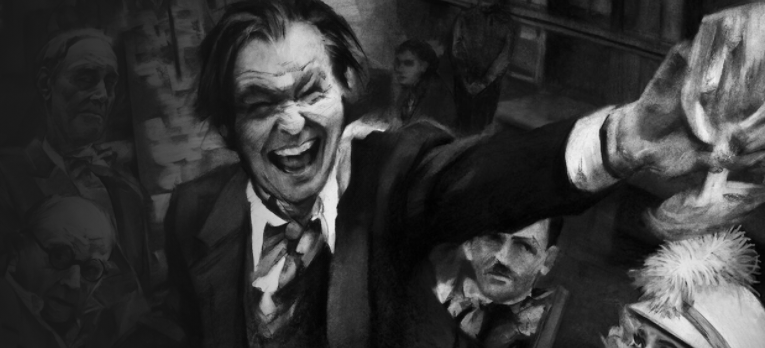

Gary Oldman gives a convincing performance as the titular character, portraying Mankiewicz as a portly alcoholic man with a brilliant mind, a quick wit, and a (mostly) reserved demeanor. One of Oldman’s best scenes comes near the end of the movie when Mankiewicz arrives at a dinner party and goes off on a 7-minute drunken tirade in which he insults several of his coworkers while attempting to pitch the idea that would become “Citizen Kane.” Oldman does not hold back in this scene, showing the audience a side of Mankiewicz that he had previously kept concealed.

Another notable performance is that of Amanda Seyfried, who plays Marion Davies, a leading actress who has a unique relationship with Mankiewicz. Mankiewicz’s wife Sarah (Tuppence Middleton) describes Mankiewicz and Davies’ relationship as a “silly platonic affair,” and Oldman and Seyfried certainly establish something to that effect over the course of the film.

Their relationship is not romantic, but from their scenes together, it is clear that Mankiewicz trusts and confides in Davies, and that he likes her more than anyone he works with; similarly, Davies respects Mankiewicz for being a lone wolf and always thinking for himself, and admires him for his brilliance as a writer.

Still, where “Mank” truly shines is in the technical department. As far as visual effects are concerned, the film’s use of a black-and-white filter stands out immediately. I must admit that before watching “Mank,” I was worried that the black-and-white filter would seem out-of-place as if it was just thrown over a modern movie that should have been shot in color. However, this was not the case.

The creators clearly paid a high level of attention to detail in order to make the film really seem like a period piece — the costumes, score, and sets are all on point — and as a result, black-and-white works. Because the other elements are done correctly, the filter serves to complement, not overpower them, which makes it all the more effective.

The film’s cinematography also highlights key elements of the story. For example, during one scene, the camera briefly shows Mankiewicz lying in bed before panning down and focusing tightly on a bottle of liquor as it rolls out of his limp hand and hits the floor with a resounding thud. A close-up with focus is not at all a revolutionary technique, but I mention it here because it is used very rarely in “Mank” — only when it is necessary to draw attention to an important characteristic, such as Mankiewicz’s drinking problem.

In “Mank,” scene transitions are accompanied by stage directions, typed across a black screen, that inform audiences of the setting of the following scene. This technique is not used just for show — I found it necessary to rely on these directions to keep track of what was happening when, since the movie is non-linear and spends about equal time in flashbacks and in the present (1940).

Even with these transition cards, I found the events of the movie hard to follow at certain points, especially as the movie jumps around before reaching its high point, Mankiewicz’s drunken rant.

And now, the burning question: should you watch this movie? The short answer is yes. The long answer is it depends on who you are and what you are looking for in a movie. I would definitely recommend “Mank” to fans of “Citizen Kane” and other Golden Age movies. For more casual movie-watchers, or really for anyone who is not well-versed in the history and central figures of 1930s Hollywood, I would say give it a try, especially if you are willing to appreciate a well-made movie regardless of subject matter – but be prepared to be confused at times.

Grade: B+

Vikram Jallepalli is a senior at Pelham Memorial High School. Writing for the Examiner is his first role in journalism. He performs in Sock’n’Buskin...