Seeing through a shrinking pinhole, ‘TB Terminator’ Bill Jacobs continues breakthrough research

As Pelham resident William “Bill” R. Jacobs walked past the zebra enclosure at the Bronx Zoo in 1990, he raised his nose and sniffed the air. “I smell phages,” he said. Jacobs scooped up a pile of dirt from the pit and put it in his pocket. Back in his lab at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Jacobs used this dirt to isolate the bacteriophage he names Bxz1. To anyone that didn’t know Jacobs, this would seem incredible. Why? Bill Jacobs was going blind.

Jacobs was born and raised in a steel mill town near Pittsburgh. As soon as Jacobs started to walk, his mother noticed that he would bump into things. She brought him to eye doctors when he was three years old where he was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa, a degenerative genetic disease that causes a loss of peripheral vision. When Jacobs looks at another person, he can only see one eye at a time.

“I grew up in the Sputnik era,” said Jacobs. “I wanted to be an astronaut. But because of my eyes, I have these lights, and I couldn’t see the stars at night.”

Nonetheless, Jacobs knew he wanted to be a scientist. In ninth grade, Jacobs’ biology teacher encouraged him to do research. His project was to test whether the plant growth hormone gibberellic acid could make chlorella grow more quickly. In 1969, Jacobs went to the Pennsylvania Junior Academy of Science competition and won an honorable mention.

However, when Jacobs arrived at Edinboro University, he decided he couldn’t study biology.

“I was trained as a mathematician,” said Jacobs. “The reason I was a math major was because I can’t memorize unrelated facts. I have to derive everything. When I interviewed with Roy Curtis III for a Ph.D. program at University of Alabama Birmingham I said, ‘By the way Roy, I don’t know much biology, I’m a math major.’ He said to me, ‘There’s no sin in being ignorant. The sin is to remain ignorant.'”

During his Ph.D. program with Curtis, Jacobs researched leprosy.

“The big killer in the world was tuberculosis,” said Jacobs. “Barry Bloom was here (at Albert Einstein College of Medicine), and he wanted to make BCG, the TB vaccine, a multivalent vaccine. He wanted me to figure out how to put DNA into it so we could protect children from TB, malaria, and all sorts of diseases at once.”

When Jacobs came to Einstein in 1985, not much was known about one of the developing world’s most dangerous killers. The BCG vaccine was discovered in 1921, but no scientist knew how it functioned. This was because in order to study Mycobacterium tuberculosis, genes needed to be inserted into the tuberculosis cell. Until Jacobs came into the picture, no one knew how to do this.

Bacteriophages are viruses able to enter bacteria and transfer their DNA into them. Jacobs decided to take dirt from his backyard in the Bronx to look for these “phages”. In 1985, Jacobs found the Bronx Bomber, or Bxb1, a phage now used in 54 papers.

By 1987, Jacobs was able to genetically manipulate phages like Bxz1 and Bxb1 and insert them into Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) to study TB. After this accomplishment, Jacobs’ research took off.

In 1993, Jacobs inserted a gene that makes fireflies glow into the TB bacterium. By looking at whether “the lights turn off,” scientists were now able to study the efficacy of drugs. Recently Jacobs made another breakthrough discovery in the TB field.

INH is a drug that is commonly used to treat TB. However, patients need to be treated for six months. Using phages, Jacobs discovered that 99.9% of bacteria died within three days of treatment. The .1% that remained were what he called persistors. He discovered that by treating TB with INH and vitamin C, persistors could be killed, shortening treatments to one month.

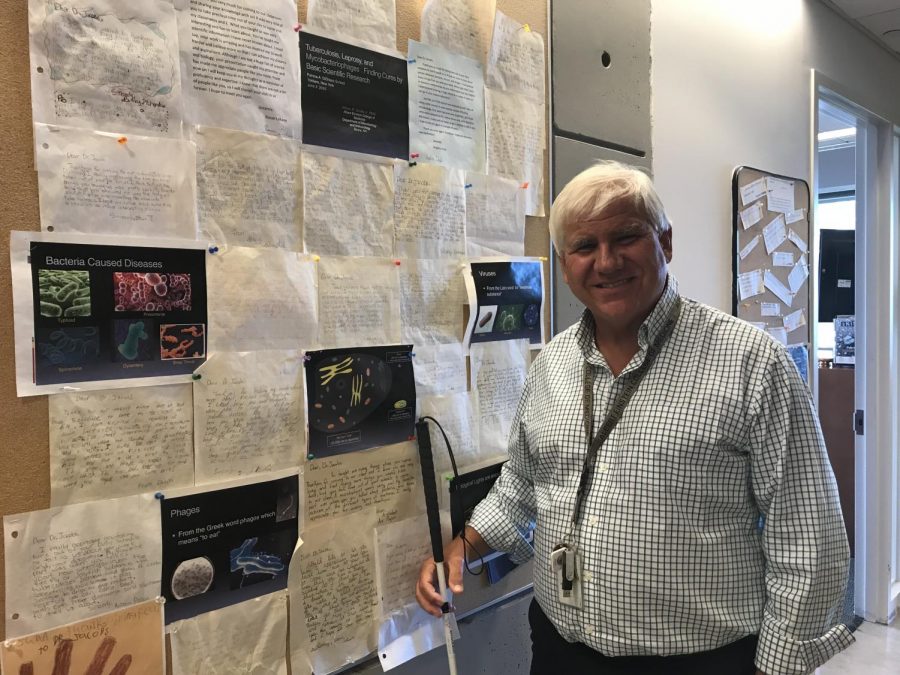

Besides leading breakthrough research that led Jacobs to be dubbed “the TB terminator,” Jacobs devotes his life to helping others. Jacobs has started several organizations that allow high school students, college students, and students in developing areas of Africa to isolate their own phages.

“Lindo grew up in an Azulu village,” he said. “She was the first woman in her village to get a college degree. She was the first person who isolated a phage in the program. She’s now a professor at the University of Pretoria.”

Jacobs’ wife Lyn is the president of the Rotary Club of Pelham. The Jacobs are part of a program that finds children from developing parts of the world that are at risk of dying from heart disease and need surgery. The Rotary Club raises money to bring these children to hospitals to receive these surgeries at a dramatically reduced cost. Jacobs has housed several of these children and regards the experience as life-changing.

It is incredible to see all the work Jacobs has done, and yet it’s hard to believe he’s done it living with retinitis pigmentosa, a disease that prevents him from even being able to see through a microscope.

“I’m night blind,” he said. “A lot of places in the developing world have low lights. On one of my trips in Africa, I was looking for a restroom, I made a wrong turn, and ended up falling down the steps. I could have killed myself. I was on a plane and I was sitting next to one of my colleagues, and I tell her ‘It really sucks going blind.’ This gentleman taps me on the back and says to me, can I come talk to you? I didn’t realize he was blind until he knocked over my glass of wine. He told me he was a supreme court justice for the constitutional court of South Africa. I said, wait a minute, how in the hell did he write the briefs?”

Inspired, Jacobs hired four personal assistants to read his emails when he came back. He now has a software on his computer that reads him journal articles and a big yellow keyboard to help him type. Whenever Jacobs needs to help someone edit their paper, he has them read it out loud.

Regardless of the support system Jacobs has built himself, it wouldn’t be enough for most people to accomplish what he has.

“I love what I do,” said Jacobs. “I mean come on, could you tell today, as I tell you this stuff, that I love what I’m doing? FDR had polio, and he decided that wouldn’t let that stop him. He rehabilitated himself and ended up being governor of New York and then president for four terms. My point is, we all face challenges. Your challenges are different than mine, but it’s a matter of willing yourself to get things done.”

Francesca Di Cristofano’s journalism career began in 2011 as a founding editor of the Colonial Times. She is now a senior at Pelham Memorial High School...

Michael Glickman • Sep 12, 2018 at 12:15 pm

What a wonderful article about Bill and Lyn. I would like to offer an additional tribute to Bill from the perspective of one of his former trainees and a Pelham resident. I am myself a Tuberculosis researcher and was a postdoctoral fellow in Bill’s lab. The article beautifully captures his optimism and achievements. Here are some additional anecdotes that illustrate the same points.

Although academic science is, in its purest form, a noble pursuit of knowledge to better the human condition, it is also a highly competitive business. Researchers compete with each other for key findings. Bill has created many of the research tools that we all use, tools that have advanced the Tuberculosis research field for hundreds of colleagues. From the beginning, Bill committed to sharing these tools with everyone. This commitment was based on his desire to move the field forward and help solve the Tuberculosis problem. Many others would have held these tools privately to maximize benefit to themselves, but Bill understood that the only way to make progress is to work together.

In the same way that we pass on our knowledge and values to our children, mostly by our example, scientists have “families”: lineages of training. Bill allowed all of his trainees (his academic children) to continue to work on their scientific projects as independent faculty members. In this way, he helped launch many independent investigators because these trainees did not worry about competing with a famous former mentor. As a beneficiary of Bill’s generous approach as an independent researcher, I have passed this tradition on to my own trainees.

He is truly a gem of Pelham, but of the scientific community, and I applaud the Pelham Examiner for highlighting not only his achievements, but his approach and attitude.

Toni Kavanagh • Aug 27, 2018 at 7:32 pm

Simply a magnificent man

He is unsssuming, brilliant, friendly, kind and magnanimous