School board’s move to expand search and interrogation powers lacks transparency

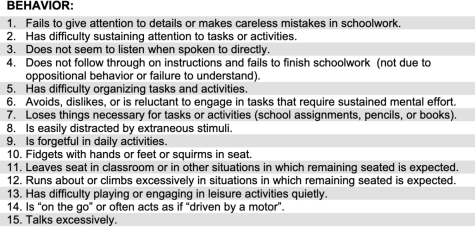

At this coming Wednesday’s meeting, the Pelham Board of Education is due to conduct a third reading of revisions to Policy 7330 regarding “Searches and Interrogations of Students,” which would allow the policy to be significantly updated from the current version that has been in effect since 2012. The current policy provides the framework for school officials to search students for “prohibited items” when a school official “ has reasonable suspicion to believe the student has engaged in or is engaging in activity which is in violation of the law and/or the rules of the school (i.e., the District Code of Conduct),” and to interrogate, strip search and refer students for police action.

It is not in question that the school board should maintain policies to protect the student body and preserve good order. But when time and money is expended to update outdated policies, it should be considered whether the new policy serves the public (parents, students and community alike) rather than whether the update is just a check-the-box exercise to conform to established school law and modernize language.

While the school board presents the near-final policy as updates in due course, the board’s discussion of the revision has lacked transparency on significant changes. The board of education and its policy committee’s public discussion falls short of the kind of engagement expected from professionals who are experts in dealing with children, who have hired professionals with expertise in social work and child psychology, and who should be working collaboratively with parents.

The first reading of the new policy was at the board meeting on Oct. 21, where Eileen Miller, a trustee and the policy committee’s chairwoman, indicated that drafting the changes to the policy started in 2019 and included addition of “school trips” to the policy (so that it is clear, the school’s authority to search and interrogate extends to activities outside school), removal of gender specific pronouns (as is now standard practice with all policy revisions) and addition of reference to “parental relationships” rather than just parents. She further added that the “general gist” of the policy remains the same as it is currently written.

At the second reading of the policy on Nov. 4, Miller said the policy committee would take another look at the policy through the lens of feedback from the school’s equity audit to see if the committee is heading in the right direction with language. In response, Superintendent Dr. Cheryl Champ suggested changing the wording in the policy to remove “interrogation” and replace it with “questioning” in order to decriminalize the policy’s language. Miller indicated a third reading might be postponed if additional changes were considered to the policy. As of the time of publication, the third reading has not been postponed.

A comparison of the current and proposed policy indicates the changes pushed through by the school board and policy committee are quite a bit more significant than articulated at public meetings. For example:

1. The new policy removes recognition that students are “protected by the Constitution from unreasonable searches and seizures,” which, to a certain extent, they are. This language is now stricken.

2. The previous policy allowed searches and interrogation of students only by a limited set of individuals: the superintendent, principals, assistant principals and the school nurse. The new policy allows any other designees of the school to conduct a search and interrogation of students, including coaches, advisors, and staff chaperones.

3. The new policy introduces the concept of a “reliable informant” who provides information to the school official on which basis a search or interrogation occurs. The information provided by an “informant” is considered reliable under the new policy “if they have previously supplied information that was accurate and verified, they make an admission against their own interest, or they provide the same information that is received independently from other sources.”

4. The new policy also allows a “District employee” to be considered a “reliable informant” unless “they are known to have previously supplied information that they knew was not accurate.”

5. The most striking change to the policy is a new step in the interrogation process that states that before conducting a search, a “school official should attempt to get the student to admit possession of physical evidence, that (the student) violated the law or the code of conduct, or get the student to voluntarily consent to the search.” The policy goes on to say that student consent is not required to conduct a search.

6. To the students’ benefit, the new policy indicates that a strip search is almost never justified unless there is “highly credible evidence that such a search would prevent danger or yield evidence.” The new policy adds that in such circumstances the school official “will attempt” to notify a parental relation by telephone before conducting the search “or in writing after the fact.”

7. In the new policy, only if there is an emergency situation that could threaten the safety of others will “police and parents be contacted immediately.”

8. To round out the involvement of parents, the new policy indicates that a parent will be notified after the fact of any items found as a result of a search under the policy and that the school has a right to “question and/or search the student without the permission of the parent/person(s) in parental relation,” further highlighting that parents will only be given an opportunity to be present during “police questioning.”

9. The policy continues to reference that a cooperative relationship will be maintained by the school administration with law enforcement, but cautions that “Miranda warnings” are not required to be given by school officials to students, even if police are subsequently called.

Who is to say the procedures implementing the policy will not be just as unthoughtful? Where is the discussion about what controls are in place, how staff will be trained for these situations and how social workers and counselors will be used to minimize impact on students? Without a requirement to contact and engage parents, who is to say that parents will not find out about a search and interrogation of little Timmy days after it has already taken place? What sort of policy tells a school official in a position of power, and likely two to five times the age of the “interrogated” student (who can range in age from five to eighteen), that the first step is to get the student to admit unlawful behavior? If the board of education and the policy committee do not have the time and resources to commit to a thoughtful review and engagement, the old policy is likely just as good.

Laurian Cristea is a resident of the Village of Pelham, father of three school-aged children and a lawyer. The Pelham Examiner welcomes commentaries from readers on issues of local concern or interest.