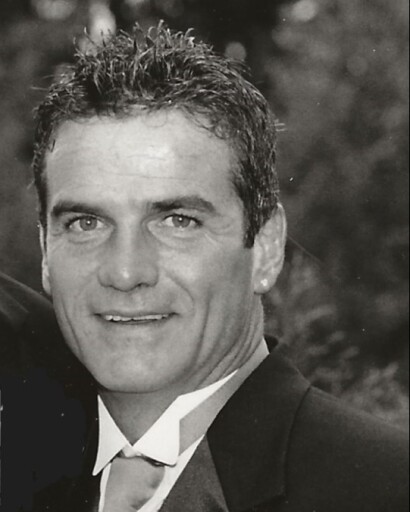

Louis Juden Reed – Dec. 11

Louis Juden Reed, MD 10/26/1934 – 12/11/2020. This obituary was written by Dr. Reed’s son; Juden Justice Reed,

Louis Juden Reed, MD.

I introduced my father with the letters “MD” after his name because there is simply no other way to think about him. Some people might insist on their degree being emphasized as a matter of status, but for my father, the call of the medical profession was inseparable from who he was all his adult life.

There was a boy before there was a man. He wasn’t a doctor, he was the son of a lawyer who paid his way through law school playing the trumpet on trans-Atlantic cruises, who served in the Judge Advocates Corps of the US Army all through WWII, leaving my dad and his beloved older brother Ronald in the care of their mother Sally. The two boys led a very active life together, including scouting and hunting with their mother’s two brothers. Sometimes too active, like the time my uncle knocked out my dad with a piece of wood off the woodpile – all in good fun, mom!

My dad graduated from the Central High School of St. Joseph, MO. He broke with the family tradition of attending University of Missouri as his father and brother had and instead attended

Washington University in St. Louis. There he distinguished himself in English, History and the sciences. A slight lad, he nonetheless joined Phi Delta Theta, at that time the fraternity that contained most of the varsity football team. They still have a photo displayed in that house of him looking impossibly young, up on the shoulders of his fraternity brothers, clutching a large trophy, which the fraternity had won for their adaptation of “Shane” for Thurtene Carnival, an annual honorary charity event. My dad wrote and directed the adaptation. In later years, I asked him why a slender lad like him, not a tall person, had been welcomed into the football fraternity, he laughed and replied “well, somebody had to do the homework!”

It was not a sure thing that he was going to medical school. In fact, he came very close to having his admission to medical school revoked when he received a poor grade in organic chemistry as a graduating senior. He spent the entire summer before beginning medical school in remedial organic chemistry, sweating bullets. I mention this because it is very easy to picture him as a medical school professor knowing what we know now, but he was not born wearing a white coat with a stethoscope around his neck. (For those of you still early on your life path, do not be discouraged from your worthy aspirations by momentary setbacks.)

About his medical school days at Washington University School of Medicine I have limited information, but he once related a story about how even then, he liked to bring his work home with him. As part of his anatomy instruction, he had to dissect a fetal pig before they attended the dissection of a human cadaver. (In those days, there weren’t enough cadavers for medical students to each dissect their own, so they learned on a pig, then watched the professor dissect a human cadaver.) My dad somehow fell behind on that project, so brought the pig home to his medical fraternity and put in in the kitchen refrigerator to dissect later. His roommates took exception, and my father returned to find the piglet swinging from a noose, bearing a suicide note. Undeterred, my father continued to bring his work home the rest of his life.

My father’s career took him to Albert Einstein College of Medicine, and the Jacobi and Montefiore hospitals in the Bronx, NY, for his internship and residency. This was the beginning of a 61-year affiliation with these institutions. While there, he married my mother, who he had met in college. She was a recent occupational therapy graduate of Wash U. He also began his lifelong love affair with the NY Metropolitan Opera, as well as the many theaters, musicals, museums and symphonies of New York. Truly, the city was a smorgasbord for a Missouri boy whose only prior introduction to opera was a series of NBC radio broadcasts live from the stage of the NY Metropolitan opera famously sponsored by Texaco. At this time, I was born and then my sister.

A fellowship was offered that took my father and his young family to London for a year. He worked to become a specialist in blood diseases at Hammersmith hospital that year. Importantly, he met lifelong friends who were his neighbors on Tibbets Close in Wimbledon: Gordon and Patricia Saggs, who immigrated to the United States when my parents returned, and who were frequent weekend visitors for many years.

Upon returning from England, my father moved the family to Greenwich, CT. Still penniless, he found a situation where we could live above the converted stables of an estate whose owner had a son my age. My mother in particular loved suburban Greenwich. I remember she cried the day a letter arrived for my father from the Selective Service System advising him that he had been drafted into the US Army for the Viet Nam War. He went to basic training in Texas and the family subsequently rejoined him when he was posted to Ft. Knox, KY at the rank of Captain.

Ft. Knox was an unexpected watershed in my father’s professional life and lifelong friendships. The Army wisely assigned him to medical research and kept him on the base for two years. No surgeon, he would have been much less use near the front lines. But at Ft. Knox, he worked on a team that helped the Army solve a very real problem: the Army kept having to discard blood that was donated for soldiers requiring transfusion. The blood just went bad too quickly. During my father’s two years in Ft. Knox, they developed a new method for storing blood plasma that increased the storage time to roughly 35 days, and which later was adopted by the Red Cross as an international standard. This was not my father’s discovery alone — he was part of a team effort that had been underway since WWI, in one form or another — but it is emblematic of him that he went into a bloody war and found a way to help people live and survive.

Anyone who has ever seen M*A*S*H knows that the Army needed doctors much more than doctors needed the Army. Fort Knox was no exception. The doctors there were highly educated, cultured intellectuals, marooned by their government in rural Appalachia. Naturally, they banded together. Indeed some had already crossed paths in their previous medical training, but in their time in the Army, became life-long friends, and their families as well. Lenny and Lorraine Dauber, of NYC. Walter and Marcia Goldfarb of Portland, ME. Frank Bunn of Morristown, NJ, Dr. Schlosser of Edina, MN, and many others whose names have blurred with time. My family went on annual ski vacations to Big Squaw Mountain in Greenville, ME each year with the Goldfarb family, at times accompanied by Houck and Kate Reed, my father’s nephew and niece.

When my father left the US Army, he moved to Bronxville, NY and returned to Albert Einstein College of Medicine as an Associate Clinical Professor. At this time, his career moved away from medical research and my father focused on what became his lifelong passion: treatment of the gravely ill with cancer and blood diseases. He and Lenny Dauber were founders of Tenbroeck Medical Associates and built a building for their practice at 1180 Morris Park Avenue, adjacent to the hospital.

It is no overstatement to say that my father lived for this calling. Many nights he stayed at the hospital rather than return home for dinner, or returned to the hospital after dinner, only to return home in the wee hours. He fought bravely to earn his very sick patients a little more time to put their lives in order: weeks, months, sometimes years. So many of his patients were deathly ill before they ever came to him, as a boy I marveled that all his patients seemed to die. I asked him once why he did this work, instead of some sunnier path in medicine where ones’ patients might live long happy lives for many years. He said that however much time he could get them was extremely important, not just for the patients, but for the families that would survive them. Time to arrange for the care of loved survivors, the education of their children, time to look to their spiritual condition.

Even for patients that had been moved to quaternary care, made comfortable at their end, he took an interest in helping the patient settle their affairs. I remember one occasion where he was reprimanded for arranging a wedding for a dying construction worker. The man had never married his partner of many years, and she would only receive union benefits as a widow if she were married, so he phoned a priest and had him marry the woman to the patient on his deathbed. This was a violation of some hospital policy or another, but my father was unrepentant. He was interested in the greater good.

My father was religious during my entire life. He served as a deacon and usher at the Reformed Church in Bronxville, NY while I was growing up. He was also an idealist who believed that a better world was possible. At times his idealism frustrated me, the young pragmatist. But he always believed in the best in people, and saw God as the prime mover of good in the world. He saw to my religious education as a youth, and he set an example of scrupulous devotion all his adult life. Which is not to say he was a teetotaler, or some species of God-botherer. He was just a profoundly good man who sought to understand and do God’s will. For him this meant helping others.

After 35 years of marriage to my mother, she requested a divorce. Despite his pleas, she was adamant and so he embarked on a new chapter of life. I was married with young children and living in California at this point, working my legal career, but we stayed in close touch over the next couple years and there was a curious role reversal as he contemplated dating as a grown man. Ever sensitive, he asked me if I thought it was a good idea for him to date. Of course I said yes and asked him if there was anyone special he had in mind. He said yes, there was this one very special oncology nurse that he admired. He said she was the best oncology nurse he had ever met, but I suspect this was only part of the reason he found her intriguing. I have heard various versions of the time my dad first asked Anita Sarthou for a date, but suffice it to say that once she got over her shock, she said yes and that turned out to be a very good thing for both of them.

Few people get to have two families, but as second chances go, my dad hit the jackpot. Annie had three sons in the Philippines from a prior marriage who were living with her sisters’ family. Once she and my dad were married, they reunited Annie with her children and my dad became known as “Uncle Juden” and it is hard for me not to smile as I say those words. He took the education, moral development, and welfare of Annie’s boys as seriously as he had taken my own. He also converted to Catholicism at the time of his marriage to Annie and I still recall my bemusement being contacted by an ecclesiastical canon lawyer who explained that his earlier marriage to my mother needed to be annulled so that he could marry Annie — but wait, what did that make me, if I consented to such a thing?! – fortunately for my dad and Annie, I am not a stickler for these things (and have some sense of humor), so I consented and they were married a second time by the Catholic Church. All to the good.

Annie was a marvelous match for my father. Fun, outgoing, full of mischief, but she also understood his commitment to medicine and had her own driving desire to work and call to heal. They were a dynamic duo together, who nonetheless found time to visit Annie’s many family and friends in the Philippines, to go skiing together and host family ski trips in the Rockies and Canada, and to tour the opera houses of Europe and Russia. In time, each of Annie’s boys married, and Uncle Juden got to be a grandpa all over again.

Although my father retired from the private practice of medicine some years ago, he never stopped working or indeed teaching medicine. I went to his first retirement party. And his second. As the third one rolled around, I got wise and realized he would only be retired a matter of weeks, and sure enough, he was back at it. He volunteered in the city hospitals, taught residents in the city hospitals, where no patient is turned away, and where he got to see the really interesting cases. Quickly indispensable, they would find him a paycheck, and two days a week would turn into three or five.

It was my father’s gift to remain mentally keen, even as his hearing declined, his balance wobbled, or his age otherwise caught up with him. I asked him if and when he planned to finally hang up his white coat and he said he would certainly do it the moment he thought he was making mistakes. He pointed out that the other doctors were quite vocal if they thought he wasn’t up to the task. But he was always very good at what he did, and he knew he was helping people, and that there weren’t enough doctors in the city hospitals. The week before he fell ill with Covid-19, my father was positively tickled to be called in for three oncology referrals. He was quite proud of himself at age 86 to be practicing medicine for those who needed it most. As fate would have it, he went down with his boots on and never had to really, actually, finally retire. So he remained Juden Reed “MD” until the end.

He is survived by his loving widow, Anita Reed, her three sons Paolo (Rose)(Lucien and Caelum), Don (Jennifer)(Zoey), and Rey (Michelle), and his two children from his first marriage, Justice (Liz)(Gordon and Julia) and his daughter Christy, whom he loved very much and with whom he was in daily contact all his days.

We will all miss him terribly.

My father touched many, many lives and influenced and encouraged many careers. It is literally impossible to list them all. Certainly, as his son, I have had to share him with a great many people! There are so many wonderful stories I could tell about him, and wish I could fit them all here, but it would be a book and not a remembrance. Please tell your stories about him and know that he loved each of you.

In Lieu of Flowers donations may be made in Dr. Reeds name to St. Catharine’s Church, 25 Second Avenue in Pelham New York.

A Celebration of Life will be held Friday, Dec. 18, from 4 p.m. to 8 p.m. at the Pelham Funeral Home, 64 Lincoln Ave., Pelham, New York. A Mass of Christian burial will be held Saturday, Dec. 19, at 9:45 a.m. at St. Catharine’s Church, 25 Second Ave., Pelham, New York.

Editor’s note: The text of this obituary was provided by the Pelham Funeral Home.